Previously, we discussed the idea of tight upper traps due to them being overly lengthened. This is very common in not only swimmers, but a lot of other athletes, too. If you haven't read part 1 yet, you can find it HERE. Today, we're going to discuss why upper traps get tight for the a different reason: they're always "on." Bear in mind, a muscle can feel tight for generally two reasons: 1) the muscle is overly lengthened, or 2) the muscle is always on. Part 1 covered the former, and now we'll cover the latter.

Why scapular elevation can occur

Going back to the idea of an ideal scapular resting position covered in part 1, we'd like to ideally see the top of the shoulder blades positioned slightly below the T1 vertebrae. If an athlete has elevated shoulders, you'll see them resting above T1. This is usually pretty obvious when you see it. The athlete will generally look like they're always shrugging.

In the swimming population, we see this a lot more in flyers than other strokes, but that doesn't mean it can't happen to swimmers with other predominant strokes. After having done hundreds of individual evaluations, we have seen many different presentations on athletes with similar backgrounds and training histories.

There are a couple of different reasons for this. How the athlete does the swim stroke is certainly one reason. If the way the swimmer does a stroke results in a higher involvement of the upper trap, and the swimmer was to repeat this motion dominating with the upper trap over and over again, it will facilitate the upper trap to work more for scapular upward rotation, which occurs any time an athlete brings their arm over their head. If you take that motion and repeat it over and over again, you get not only a dominant muscle, but also a dominant motor pattern with overuse of the upper traps.

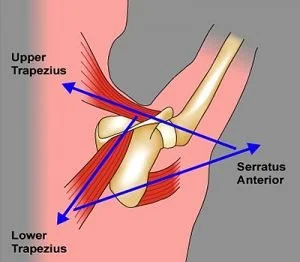

Typically, you'd want other muscles like the lower trap and serratus anterior to help with this. We have found that the majority of our swimmers that have this type of presentation have a very difficult time recruiting their lower traps and the upper trap takes over for a lot of the movement of the scapula. It often takes manual positioning of the scapula during certain exercises for the athlete to feel the lower traps work.

Another reason you may see this is a breathing strategy. Seeing as the average person takes about 20,000 breaths per day, and breathing is necessary to survive, the body prioritizes breathing above everything else. A poor breathing strategy can lead to a LOT of changes to the human body, one of which is posture. If you sit and take a deep breath, most people are going to notice substantial elevation of the shoulder girdle. Go ahead, try it. Take a breath in and notice what happens. Did your shoulders rise up closer to your ears? I bet they did. An ideal breath would involve mostly circumferential expansion of the thorax. As an aside, an ideal breath is NOT belly breathing. The rib cage is meant to expand on inhalation.

If you take a breath, and your upper body elevates quite a bit, there are muscles that are doing the elevating. Some of these muscles are: upper trap, sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, pec minor, levator scapulae, and subclavius. All of these muscles elevate the ribs and can elevate the shoulder girdle. When they're being overly recruited to breathe every day, they tend to get stiff and tight. Take for instance someone who complains of always holding “stress” in their neck and upper back. What they’re actually doing is overusing their neck muscles to breathe. When these muscles are stiff and tight all the time to breathe, you better believe they'll affect not only your resting posture, but also how you complete certain movements.

What do you do about it?

While there is some debate as to whether or not self-myofascial release techniques such as using a lacrosse ball or foam roller actually work, it makes our athletes and clients feel better, so we still use them with every person that comes to Achieve. For the issues described above, we'll typically roll the upper traps, lats, pecs, rotator cuff, levator scapula, and some others areas.

In addition to this, we want to get the right muscles to be positioned to function best, so that generally means a few breathing exercises meant to put the scapulae in the right position, reduce muscle tone of the upper traps, facilitate the serratus anterior and lower trap, and get circumferential expansion of the thorax. This is usually a multistep effort and is likely not to occur within one session. We'll often program sequential exercises to target one or more of these goals at a time, and then use other exercises to integrate them into movement.

Exercise selection and coaching are important here as you don't want to hinder an athlete's progress by giving them inappropriate exercises that will push them back into the position they were previously in. We like to start out with lower-level exercises that involve recruiting mid and lower traps and the serratus anterior. With respect to coaching, we're mainly concerned with movement patterns that involve the upper trap and making sure it doesn't dominate the movement. Some of these exercises include landmine presses, rows, and overhead carries. We're careful to ensure on a row, for example, the athlete isn't getting the shoulder blade to elevate as it's moving toward the spine during retraction. After all, the most important job of a coach is to actually coach in a meaningful way that gets the desired result for the client or athlete.

Wrap up

The key to managing truly tight upper traps alongside scapular elevation is to determine the possible causes and attack them through programming and coaching. And, of course, this all starts with a thorough evaluation in the beginning to uncover the possible reasons why a swimmer (or other athlete) likely has the issue in the first place.